From permissive to tense: Sunni Baluchs and their relation with Tehran

By Hessam Habibi Doroh

Editor’s introduction

In September 2022, the death of Mahsa Jina Amini marked a major turning point for Iran. The event sparked nationwide protests that rapidly evolved from calls to discard controversial hijab regulations to calls to overthrow the Islamic Republic. The Iranian government responded with repression, killing over 400 protesters in late 2022 and early 2023, according to human rights groups.

The Clingendael blog series ‘Iran in transition‘ explores power dynamics in four critical dimensions that have shaped the country’s transformation since: state-society relations, intra-elite dynamics, the economy, and foreign relations. This blog post analyzes the relation between Iran’s Sunni Baluch and the state, focusing on its socio-political elements.

Putting Iran’s Baluch population in perspective

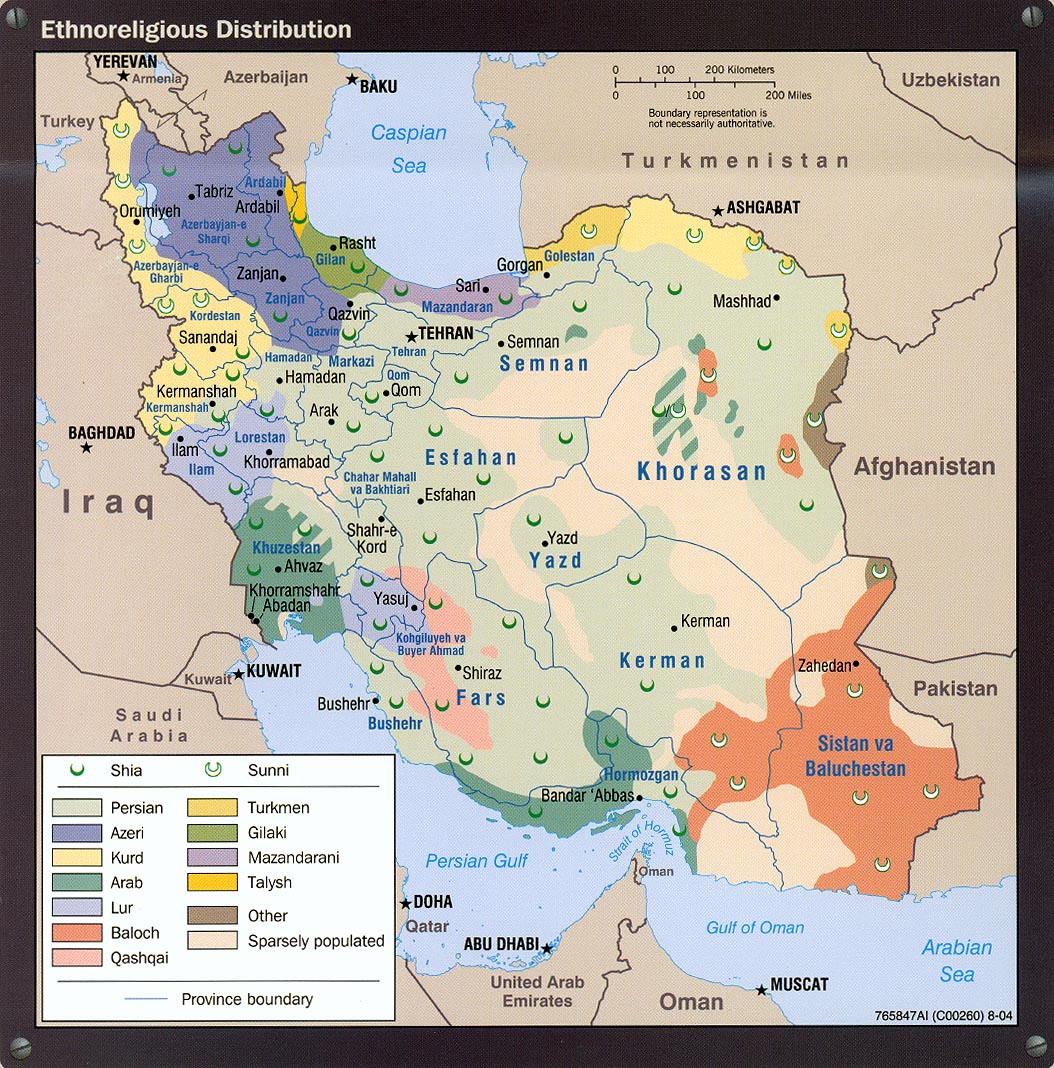

Iran’s Baluch community is notable for its diversity (c. 3 million or 4.5% of its total population). For example, at least two distinct intellectual groups exist within this community. The first group comprises educated and secular Baluch while the second group consists of religious Baluch who also represent a part of the community’s elites – e.g. those with strong religious affiliations across Islamic communities in South Asia. The Baluch population is primarily concentrated in the border regions of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Most adhere to the Hanafi branch of Sunni Islam, although there is a small number of Shiites. The crystallization of Sunni Baluch identity that commenced in the mid-1930s significantly altered the community’s social hierarchy. The local Khans and Sardars (chiefs and protectors of tribes) were gradually supplanted by religious leaders during the reign of Reza Shah, which elevated in particular the status of Molavis (Sunni clerics who had graduated from Deobandi schools on the Indian subcontinent), Ulama (Islamic scholars) and Shaykhs. As part of the state’s centralization policy, the Pahlavi administration aimed to eliminate the semi-autonomy that Baluch tribes had enjoyed by suppressing their chieftainships and by supporting Sunni religious institutions (also to counter the influence of Wahhabism and leftist secular ideologies). In this manner, the Pahlavi administration strengthened Sunni communities and their identity, promoting a shift from more secular to more religious intellectual leadership in the process. While this transformation did not eradicate the role of the tribal hierarchy, it did introduce a new social role for the Ulama, enabling them to become more involved in the daily lives of the Baluch community and to intervene in socio-political matters. This blog examines the relations of these religious elites with the Iranian state - both the monarchy and republic - to shed light on state intervention in the country’s periphery. Such interventions ultimately developed ethno-confessional identities among peripheral communities, which subsequently started to challenge the state in turn.

A new leadership in Tehran and Zahedan

Iran entered yet another new era in 1989 when the Iran-Iraq War ended and Ayatollah Khomeini, the country’s first Supreme Leader, passed away. It started with the appointment of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as the new Supreme Leader and indicated a significant shift in the political landscape of the nation, including with respect to Sunni Baluch communities. Under Khamenei’s leadership, the state increased control over education, starting in 1995 for Shia schools and extending to Sunni schools in 2007. The establishment of the Office of the Legate for Sunnis of Sistan-Baluchistan in the early 2000s reinforced this control. Concurrently, the Basij and IRGC expanded their authority in Sistan-Baluchistan.

In parallel to Khamenei’s appointment, Molavi Abdolhamid Esmailzahi, head of the Makki Mosque and Darolulum (House of Learning) in Zahedan, emerged as the leader of the Iranian Sunni Baluch and potentially all Iranian Sunnis. The Makki mosque became a centre for the revival and politicization of Sunni Islam in Iranian Baluchistan from 1990 onwards. Due to the quality of its organization and its performance, the institute became a model for Sunnis in Iran, exemplified by its annual graduation ceremony in the Deobandi style (Khatm-e Bukhari). Additionally, the Makki mosque linked many Sunni mosques and madrasas throughout Iran, strengthening Sunni identity in Iran and shaping socio-political dynamics. In part, this was possible due to the development of the “Sunni vote”, i.e. with a population of around 17 million, Iranian Sunnis constitute a sizeable electoral constituency that tends to support the Islamic left (later: reformist) and modernist conservative (moderate) politicians. Such candidates typically address minority issues – such as greater socio-cultural inclusion and recognition of rights - and advocate for more liberal policies. In brief, Iran’s Sunni have become a constituency in processes of political participation and vote mobilization.

Abdolhamid expanded the agenda of the Sunni communities of Iranian Baluchistan from its original confessional focus to include broader socio-political issues that affect all of Iran’s ethnic groups. During the 2022-23 public protests, Abdolhamid became a prominent voice addressing national issues, such as women’s rights, freedom of speech, and other socio-political issues. He also used media associated with the Makki mosque and institute to address international issues, including criticizing Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, the Taliban’s policies, and the war in Gaza. In response, state media criticized him in turn and state security forces pressured Zahedan and the institution to change tune. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Abdolhamid’s popularity continued to grow.

Political allegiances

In time, Sunni Baluchs have shown a proclivity towards the socio-cultural promises of reformists, as opposed to the traditional conservatives (principalists). For example, in the province of Sistan-Baluchistan, which is predominantly Sunni, 90.97% of the population voted for President Khatami’s second term in 2001. During this period, Iranian Sunnis achieved a degree of autonomy through the establishment of decentralized city councils. During the controversial 2009 election (due to widespread fraud), Iranian Sunnis demonstrated a clear preference for Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karrubi. Both strongly emphasized the protection of minority rights. After four years of recurrent confrontation between security forces and some Baluch communities during Mahmud Ahmadinejad’s subsequent presidency, the government acknowledged the need for more inclusive and participatory policies regarding ethnic and confessional minorities.

In 2013, a moderate politician, Hassan Rouhani, ran his campaign with the message “no intervention in minority religious and confessional affairs”. During his campaign, Rouhani often emphasized minority rights and issues. However, it is evident today that Rouhani’s reform efforts regarding minorities, particularly in relation to Iranian Sunnis, have been unsuccessful. Not only were Sunnis excluded from cabinet, but Rouhani’s promise to redress the government’s securitized view of minorities was not kept either, as were his promises for the allocation of more economic resources to the country’s minority inhabited peripheries. During his second term, minorities were in fact increasingly securitized, i.e. viewed as a security risk, or even threat. For instance, the number of arrests and executions of Sunnis from different provinces increased significantly in 2019 and 2020. In the final two years of Rouhani’s presidency, economic hardship also increased popular recourse to fuel smuggling from Iran to Pakistan through Sistan-Baluchistan, resulting in a number of fatal incidents between security forces and smugglers. The death of fuel smugglers (referred to as sukhtbar) due to the intervention of security force or accidents, were frequently highlighted in the public sermons of Sunni clerics. In a 2020 letter to Supreme Leader Khamenei, Molavi Abdolhamid asserted that Iranian Sunnis continued to experience marginalization and discrimination. They remain, in his words, “second-class citizens.”

Declining trust in systemic reforms in Tehran

As a result of such developments, the discourse of Sunni ulama in Sistan-Baluchistan towards and about the state became increasingly critical. Towards the end of Rouhani’s tenure (2019-2021), the state’s approach to Iranian Sunnis also became more securitized as a result of international and domestic pressures such as growing rivalry with Saudi Arabia and economic-military escalation with the U.S. The result was a loss of faith in moderate and reformist candidates in the 2021 presidential election. Compared to the 2017 election, Ebrahim Raisi’s vote in Sistan-Baluchistan and Kurdistan nearly doubled in 2021, while the vote for Hemmati (the moderate candidate) dropped dramatically (about 11% in Sistan-Baluchistan and 15% in Kurdistan, compared to Rouhanis 73% and 67% in 2017). However, it should be noted that voter turnout also decreased significantly in both areas (by almost 37% in Kurdistan and 17.5% in Sistan-Baluchistan). During the 2021 presidential election, the Sunni elites of Sistan-Baluchistan and other parts of Iran’s periphery showed their discontent with the country’s reformists by supporting Ebrahim Raisi. Iranian Sunnis characterized this outcome as an act of “political wrath” (qahr-i siyasi) that sought to punish the reformists and moderates for the inability to keep their promises. It was also evident that Raisi was destined to emerge victoriously, which made the choice low-cost and in fact rational in order to maintain good connections with the state.

However, the situation of the country’s Sunnis did not improve after the elections. They faced increased pressure from the Iranian state. In September 2022, reports of a Baluchi girl named Mahu being raped by a police officer in Dashtyari sparked protests. Sunni clerics in Baluchistan and Kurdistan focused on this incident during the ‘Woman Life Freedom’ movement, which gained momentum after Mahsa Amini’s death. Tensions in Zahedan were already high before the protests spread. Baluch leaders tried to address their community’s concerns, especially among youth. But as the movement gained momentum, the inhabitants of Zahedan expressed their discontent in the streets. This happened in a context of tensions between protestors and security forces since 2019. Local issues merged with national demands, which amplified demonstrations and added a new dynamic to popular discontent. The situation peaked shortly after the Friday prayer by Abdolhamid on 30 September 2023. Clashes erupted between local Baluchs and the security forces that resulted in an unprecedented bloodbath in Zahedan around the Makki complex. Over 90 people were killed and around 200 injured. The people of Zahedan call it “bloody Friday”.

Multilayered grievances

Some Iranian scholars argue that the main explanatory factor for the inequality that population groups in Iran’s borderlands face is geographic distance from the center rather than ethnic discrimination. Such inequality takes the form of resource distribution, a lack of employment and investment, and local administrative positions being held by outsiders. However, Sunnis also face confessional discrimination as a minority beyond economic issues. Even though article 12 of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran declares Islam and Twelver Jafari (Shiite) as the official religion, it also recognizes the four main Sunni schools of thought (Hanafi, Shafei, Maleki and Hanbali) and the Shiite Zaidi, guaranteeing their freedom to practice, establish education systems, and manage family affairs such as marriage and divorce.

Regardless of the fact that the same constitution includes religious minorities in the political system (articles 64 and 67), article 115 nevertheless stipulates that the president must practice Shiite Islam while post-revolutionary Iran has not appointed Sunni members to cabinet although the presidency of Rouhani saw the appointment of Sunni individuals to ambassadorial, deputy minister and gubernatorial positions. At the provincial level, city councils have done somewhat better but they continue to face top-down restrictions from above that limit even mid-level management appointments in local communities. Even at the municipal level, however, Sunni communities have not been allowed to construct a mosque in Tehran despite years of negotiation. Underneath the practical matter of “appointment” or “designation” (gozinesh), as it is commonly referred to in Iran, lies a deeper issue of marginalization. This is evident from repeated concerns raised by Sunni communities. By listening to the voices of Iranian Baluch, religious or secular, one can sense a strong feeling of alienation.

… and an unresolved security dilemma

The state’s approach to Iranian Sunnis, particularly the Baluch and Kurdish communities, has historically been mostly security-oriented. State security forces continuously suspect local mischief, prioritize border security and view minorities as political risk. In time, this has lead Sunni Baluchs to distance themselves from the state, mentally and in terms of identity, strengthening their own ethno-confessional identity instead and occasionally challenging authorities. Without undoing such securitization effects, it will be difficult to restore trust between center and periphery.

It was not always so, however. During the Pahlavi era, the state permitted Iran’s Sunnis certain freedoms in establishing their religious authorities with the aim of developing a counterweight to secular ethno-nationalist movements and preventing Iranian Sunnis from studying in Pakistan or Saudi Arabia for security reasons. Consequently, Iranian Sunnis were able to establish autonomous institutions that facilitated the expansion of Sunni identity in Iran’s periphery. In fact, when the situation in Afghanistan and Central Asian states such as Tajikistan and Uzbekistan deteriorated, Iran’s madrasas themselves became new centres for Sunni regional education and learning instead. In the 1990s, many madrasas, particularly in Khorasan, were predominantly populated by Afghan and Tajik students. But by the end of the 1990s, the state perceived this transnational engagement as a threat to the social cohesion and integration of Iran’s Sunnis. Consequentially, it initiated a series of measures to halt the inflow of foreign students to Iranian madrasas and sought to integrate these centers into state-run religious institutions. Once foreign students were banned, Sunni religious leaders in eastern Iran were obliged to attract local students to maintain the status quo and their prestige. So in brief, state intervention for security reasons prompted Iran’s Sunnis to reinforce and disseminate their confessional identity.

By the mid-2000s, the state intensified its control over Sunni communities and their religious institutions, especially through the establishment of the Council for the Management of Sunni Religious Schools. The newly established council, perceived by Sunni religious elites as unwarranted state intervention in their affairs, created a more hostile environment between Sunni communities and the state as the Council was viewed as a central attempt to establish control and influence the community’s socio-political outlooks. For example, it intervened in setting curricula and narrowed their religious content. In response, Sunni religious institutions strengthened their own interconnections. The Council for Coordination of Sunni Madrasas in Khorasan and Baluchistan provides an example of such a response.

Conclusion

A review of the last three decades of center-periphery relations between Baluchs and Tehran reveals a close correlation between the issues they face and the broader challenges of Sunnis and other ethnic groups in Iran. Interestingly, unlike the Baluchs in Pakistan, whose marginalization is primarily ethnic, Baluchs in Iran experience securitization and marginalization based on confessional grounds. Future leadership changes in Tehran or Zahedan can either dampen or amplify Sunni-Shia control dynamics. For example, the persistence of a strong Shia nationalist identity that dominates the public sphere, i.e. the constitution, official policies as well as practices of governance, combined with more security surveillance and intervention, is likely to further galvanize ethno-confessional sentiments. The question whether the Iranian state under the presidency of Masoud Pezeshkian will alter its approach and start rebuilding state-society relations – allowing the country’s Sunni to reciprocate if they wish - remains unanswered for the moment, and is contingent on the broader strategies of both sides.

Hamidreza Azizi and Erwin van Veen are the initiators of this blog series.